Shyness and Social Anxiety: From Silent Withdrawal to Strategic Support

Explore the difference between shyness and social anxiety, how cultural and digital forces shape symptoms in African and global youth, evidence-based treatments, and scalable solutions for families, workplaces, and communities. Primary Keywords: shyness vs social anxiety, social anxiety Africa, cultural stigma mental health, workplace anxiety, MindCarers

Introduction: Beyond Just Shy: Knowing about Hidden Social Suffering.

Amina, 24, lives in two worlds, namely Accra and London. She speaks fluently online, commenting on the arguments taking place in the world, and building a small business with art. In a meeting room, she practices her sentences in her mind and walks out of the event very early. Her friends call her “shy.” Her boss blames it on confidence issues. Amina does not discuss any promotion interviews.

This scenario is not unique. There exist two worlds of the youth in Africa, in the diaspora, a digitally acted-up image that is not afraid to be bold and an in-life version, where fear of being judged, humiliated or wrong about their choices affects their day-to-day decisions. It is in it that the outward ability and the inward withdrawal meet to form shyness, which can evolve to social anxiety disorder (SAD) as a disabling condition with far-reaching consequences in life (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

The line between normative and clinically relevant social anxiety must be drawn. Shyness is a personality trait, a minor discomfort in a new social environment that most members of society can manage and get rid of. Social anxiety, in its turn, is a recurrent, pervading phobia of social scrutiny, aggravating performance in the sphere of work, education and relationships (Stein and Stein, 2008). These anxieties may be repressed, misinterpreted, or even spiritualized when it comes to the case of stigmatizing emotional disclosure in cultural settings, postponing assistance and further enhancing its influence (Patel et al., 2018).

The article explains psychological and biological determinants of social anxiety, the role of culture (especially African and Afro-diasporic conditions) on its manifestation, and offers feasible ways, which can be pursued by individuals, families, schools, corporations, religious, and policy makers, that would be both practical and readily scalable. It also outlines a business-ready model, the hybrid MindCarers approach, that integrates clinical rigor and cultural intelligence to prevent and treat social anxiety at a scale level.

Shyness vs. Social Anxiety Disorder: Clinical Difference.

The personality characteristic is shyness; a mental diagnosis is social anxiety disorder. Shyness can result in a person becoming a loner or an introvert, but does not generally culminate into an experience of extreme panic or avoidance. The disorder, which is a high level of fear of social activities when the individual is exposed to criticism and avoids it or faces severe distress for at least six months or above, is referred to as SAD and is diagnosed under DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Increased amygdala reaction to social threat cues and deficient control of emotional responses by the prefrontal cortex are neurobiological processes in socially anxious individuals (Etkin and Wager, 2007). The SAD can lead to behaviours that lead to safety behaviours (e.g., restricted speech, no eye contact) to sustain fear and reduce the possibility of remedial social experience. More to the point, untreated SAD results in depression, drug abuse, and work performance (Kessler et al., 2005).

Remarkably, diagnosis is to be made according to the influence of cultural preconditions: what is superfluous in one society is habitual in another. The clinicians are then supposed to compare the distress and impairment to the local expectation,

languages, and social roles (Kirmayer, 2001).

What Goes on in Psychology and Physiology.

The complexity of the biopsychosocial interaction leads to the development of social anxiety. Genetic predispositions lead to the background that preconditions the trajectories which are the result of learning histories, early attachment, peer experiences, and traumatic experiences (Rapee and Spence, 2004). Indicatively, there is a risk of the repetitive guardedness of parents or social rejection that is habitual. The cognitive models will be based on the biased attention to the threat, negative self-appraisal and catastrophic decision in relation to social performance (Clark and Wells, 1995).

Socially, the social anxiety activates the sympathetic nervous system: palpitations of the heart, sweating, muscle shaking, and stomach ache are the norm. Victims view agony as apparent social incompetence and develop more and more avoidance (Clark and Wells, 1995). Avoidance in the long term inhibits corrective learning, and it maintains anxiety.

The cognitive restructuring is found to affect the threat appraisal; exposure therapy can be used to diminish avoidance, social skills training has been found to assist in competence building, and in some instances, medications (SSRI, SNRI) have also been found to stabilize neurochemistry (Hofmann and Smits, 2008).

Cultural Grounds: The African Contexts Have a Different Effect on Social Anxiety.

Fear and display of distress are determined by culture. Family honour, reputation of the community and relational obligations are closely joined with social roles within most African societies. Words like, do not shame the family and we are the family line are indicators of very high social stakes of failure or humiliation. This dynamic adds to the pressure of performance in the case of adolescents and young adults who are forced to deal with urban modernity and transnational identities.

The shame cultures are known to withhold the expression of individual vulnerability that leads to somatization (headaches, stomach problems), and spiritual accounts of suffering (e.g. spirit attack) (Kirkayer, 2001). Families may show faith or refer to traditional healers instead of psychotherapy, and it can be effective provided it is applied with a respectful biomedical treatment, whereas it becomes dangerous when evading the evidence-based treatment.

The other dilemma that diaspora youth must deal with is the cultural negotiation issue. They are even subjected to the penalty of stigma twice (at home, they endure cultural shame, in foreign countries, they are subject to racialized pressure), social vigilance and self-accusation are increasing (Bhugra and Becker, 2005). MindCarers emphasizes culturally sensitive assessment, which includes the model of community language and explanations in clinical practice.

Early signals: Signs that a Family and an Educator may discover.

The early realization is cost-effective and powerful. These warning signs include:

Chronic shyness (sociophobia).

• Excessive preoccupation and post-social anxiety.

Concomitants of social events, which are manifested in physical symptoms (shaking, nausea, blushing).

• Preparation or a repetitive speech or usage of notes.

Poor school or work performance, even when one is able to do it.

• Graving off friends, dating or playing on a team.

Teachers and parents may utilise gentle enquiry: they should ask questions concerning the inner world of the child and not just about his/her behaviour. Acknowledge feelings and desensitize anxiety, and take minimal actions that espouse graded exposures - small steps with support to social interactions. Formal role-plays and drama can be culturally compatible procedures of cultivating social self-confidence in most African schools.

Gender Craziness: Boys, Girls and Expectations.

Gender norms dictate the expression of symptoms. Boys are often socialised in a stoic manner and taught not to express vulnerability, and thus, this results in suppression of anxiety, which is externalised or the use of drugs and alcohol. Girls may be more closely monitored concerning morality in relation to appearance and behaviour, as well as body image anxiety and social-evaluation anxiety may rise. The intersectional issues of class, ethnicity, and sexuality expand the risks; to be more exact, LGBTQ + youth have felt ostracized and victimized (Meyer, 2003).

Gender sensitive in effective interventions: the boys’ programmes should create secure conditions to express emotion, and the problems of body image and safety and the formation of the assertive voice as per the girls. The male role models and community leaders can show balanced masculinity and actual womanhood in terms of emotional wellbeing.

The Digital Factor: Social Media, FOMO and Performance Anxiety.

The online world provides an opportunity to connect, become an entrepreneur and express oneself - yet it amplifies social comparison and perfectionism. Algorithms encourage spectacle; measurements (likes, views) fall into the category of social goods. Online presence can be both a refuge and a trap for the socially anxiety-ridden young people. They can play it with an air of confidence on one end and avoid face-to-face communication on the other, further dividing the gap between appearance and fear.

Cyberbullying, cancel culture, and shaming people enhance susceptibility. In addition, continuous exposure to edited success stories contributes to FOMO and decreases the tolerance to social mistakes of a mundane nature. The new elements of social anxiety programmes include digital literacy interventions to educate people on critical consumption, boundary-setting, and digital fasting.

When Shyness Becomes Disorder: Chronic Effects.

Unattended, SAD leads to aggression in education, employment, relations and civic participation. It reduces life options: career options are fewer, and love opportunities become less etc. In a societal setting, untreated social anxiety adds to productive loss and under- usage of talent, a key factor to be considered in emerging economies aiming to exploit the potential of the youth.

Mental health expenditure is not solely individual, but also economic. Presenteeism costs employers’ silent losses in terms of the lack of innovation and loss of talent.

Prevention and early treatment are the most profitable options: mental health programmes at work are generally found to have a high ROI in terms of lower absenteeism and increased engagement (Deloitte, 2020).

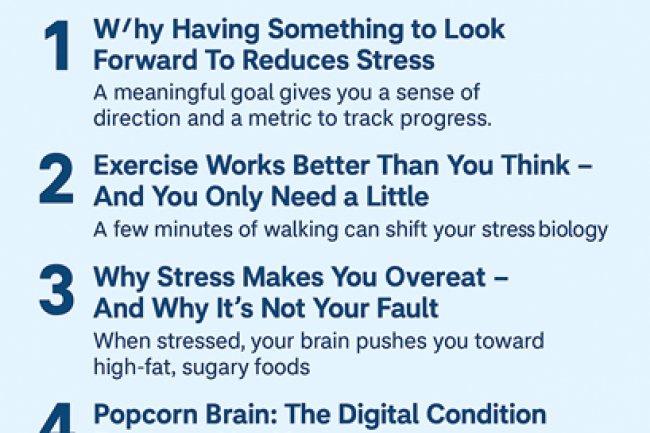

Evidence-Based Ways to Recovery: What Works.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT): There is strong evidence on CBT for SAD. Some of the primary components are cognitive restructuring, exposure exercises (gradual exposure to feared things), and communication and assertiveness skills training (Hofmann and Smits, 2008).

Exposure: Therapy Exposure (Breaking avoidance): The avoidance is decomposed using a systematic and supported form of exposure Therapy. It also has corrective social feedback and peer normalization in group forms.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): ACT assists clients to be committed to useful actions despite anxiety, and develop meaningful engagement in life (Hayes et al., 2006).

Medication: SSRIs and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) may decrease the severity of the symptoms and increase participation in the therapy when it is prescribed (Bandelow et al., 2008).

Complementary Strategies: Mindfulness, breathing practice, physical activity, and sleep disorders are used to enhance physiological stress. The means of culture, such as narration, communal practices, and religious understanding, may be incorporated to enhance a sense of belonging and significance.

Community, Family and Faith: Systems that Mend (and wound).

One of the frontline resources is families. Support can be promoted by simple strategies:

• Authenticate instead of downplaying (I can understand how difficult that must have been).

Normalization Graded steps and micro-wins are to be celebrated.

• No intrusive pressure; no encouragement of scaffolding of autonomy.

• Engage in shared customs (drama, music, stories, etc.) to perform social roles in secure locations.

When felted sensitively, faith institutions can provide a very strong recovery network. Clinician-religious partnerships - training religious leaders/Islamic clergy to be mentally health literate and referral routes - are cost-effective measures that enhance seek-help and decrease stigma (WHO, 2013). Nonetheless, it is critical to be aware of the simplistic spiritualization of mental illness that postpones evidence-based care.

Schools and Workplaces: Prevention and Accommodation.

Social-emotional learning (SEL), speaking in front of people, and clubs of peers should be incorporated into schools. The long-term impairment can be minimized by early intervention units and school counsellors.

Social anxiety must be identified as a talent risk in the workplace. Potential leadership can be unlocked by realistic accommodations in the form of flexible presentation formats, mentorship, graded exposure to visibility tasks, and so on.

Youth social skills training (internships with coaching, public-speaking boot camps) has the benefit of creating both social impact and a pipeline of talent in terms of CSR.

Scalable Solutions: Hybrid Model of MindCarers.

MindCarers suggests a preventive and treatment model: hybrid, business-friendly, collectivist-culture and business-friendly:

Digital Screening & Triage: Mobile-first tests (local languages) to detect the risk of social anxiety and prescribe customized channels.

Blended Care: Online CBT modules and the presence of group exposures in a safe community are encountered periodically in groups.

CLMS (Certified Lay Mental Health Supporters): Community mentors are providers of initial support and contact with the clinician, trained to do so.

Corporate Partnerships: Coaching, leadership confidence programme and integration of EAP by employers.

Disability & Community Inclusion: Relational training of religious leaders to identify SAD and make culturally responsive referrals.

Research & Outcomes: The ROI should be demonstrated through constant outcome measures in order to inform scale-up.

This model can be justified in the international markets since it utilizes cultural IP (Ubuntu-style collective healing) and evidence-based therapy, which provides a unique value proposition relative to Western-first applications.

Practical Toolkit: First Steps in Individuals and Families.

To individuals: graded exposure (few, planned steps of social exposure), relaxation practices ahead of stressful events, lessen perfectionism discourses, and pursue evidence-based treatment.

To families: establish predictable routines of support, promote involvement in the group activities, avoid the use of shaming language, and organize vulnerability modelling.

To employers: provide coaching to front office jobs, provision of alternative presentation formats and sponsorship of confidence-building workshops.

Conclusion: Transform Silence Social Courage.

It is a social loss when shyness transforms into debilitating social anxiety that ensures effective individuals end up playing their part half-heartedly. The need to combat SAD is both moral and developmental, and economic. It reinstates personal prosperity and opens human capital. To Africa and the world, the future lies in combining scientific excellence with cultural shrewdness, company venture with grassroots action and the internet with a human touch. The hybrid, culturally intelligent model of MindCarers can provide a way of turning silent avoidance into social courage, which can be scalable, research-grounded and locally resonant.

References (Harvard Author–Date)

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Bandelow, B., Zohar, J., Hollander, E., Kasper, S., Möller, H.-J., & WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (2008) ‘World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders — first revision’, The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 9(4), pp. 248–312.

Bhugra, D. and Becker, M.A. (2005) ‘Migration, cultural bereavement and cultural identity’, World Psychiatry, 4(1), pp. 18–24.

Clark, D.M. and Wells, A. (1995) ‘A cognitive model of social phobia’, in Heimberg, R.G., Liebowitz, M.R., Hope, D.A. and Schneier, F.R. (eds) Social Phobia: Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 69–93.

Deloitte (2020) Mental health and employers: Refreshing the case for investment. Deloitte Insights. Available at: https://www2.deloitte.com (Accessed: date).

Etkin, A. and Wager, T.D. (2007) ‘Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: a meta-analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia’, American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(10), pp. 1476–1488.

Hayes, S.C., Luoma, J.B., Bond, F.W., Masuda, A. and Lillis, J. (2006) ‘Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes’, Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), pp. 1–25.

Hofmann, S.G. and Smits, J.A.J. (2008) ‘Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials’, The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(4), pp. 621–632.

Kessler, R.C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K.R. and Walters, E.E. (2005) ‘Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication’, Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), pp. 593–602.

Kirmayer, L.J. (2001) ‘Cultural variations in the clinical presentation of depression and anxiety: implications for diagnosis and treatment’, Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62(suppl 13), pp. 47–54.

Meyer, I.H. (2003) ‘Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence’, Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), pp. 674–697.

Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., et al. (2018) ‘The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development’, The Lancet, 392(10157), pp. 1553–1598.

Rapee, R.M. and Spence, S.H. (2004) ‘The etiology of social phobia: empirical evidence and an initial model’, Clinical Psychology Review, 24(7), pp. 737–767.

Stein, M.B. and Stein, D.J. (2008) ‘Social anxiety disorder’, The Lancet, 371(9618), pp. 1115–1125.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2013) Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020. Geneva: WHO.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2022) World Mental Health Report: Transforming mental health for all. Geneva: WHO.

What's Your Reaction?