Therapeutic Intervention to Reduce Youth Crime via Mental Health Programs

Youth crime is often a symptom of deeper psychological and social challenges. This article explores how targeted therapeutic interventions—such as counseling, trauma-informed care, and community-based mental health programs—can reduce youth offending and promote rehabilitation. It highlights the link between mental wellbeing, early intervention, and safer communities.

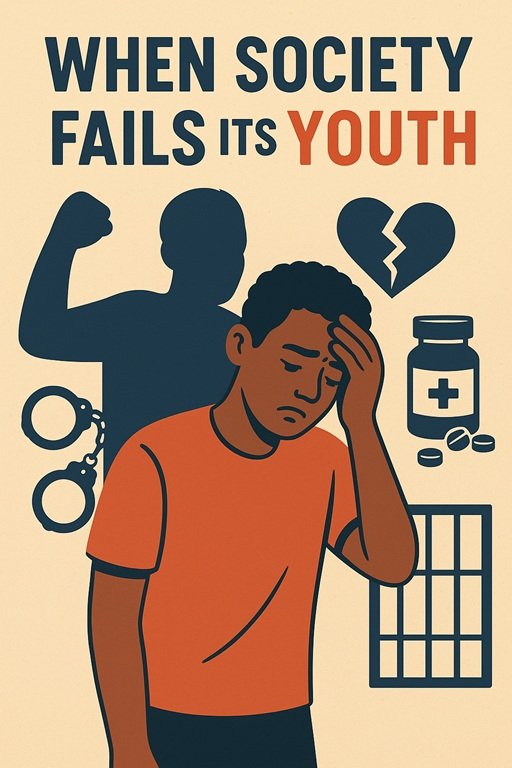

When Society Fails Its Youth

Every society’s future depends on its youth — yet around the world, millions of young people are lost to cycles of violence, addiction, and crime. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC, 2023), youth aged 15–29 account for a significant proportion of violent crimes globally.

In many developing nations, this crisis is not driven merely by moral decay but by untreated trauma, social exclusion, and poor access to mental health care (WHO, 2022).

When mental health needs go unrecognized, emotions turn into aggression, neglect becomes rebellion, and pain becomes punishment. The question is not why young people commit crimes, but what kind of society lets so many of them suffer silently until they do.

This is where therapeutic interventions — especially those built on mental health awareness, counselling, and community rehabilitation — can transform not only individuals but entire societies.

As the world rethinks public safety and justice, the emerging truth is clear: the most effective crime prevention strategy begins in the mind.

The Psychological Roots of Youth Crime

While poverty, peer influence, and lack of education are well-known contributors to youth crime, research increasingly reveals that mental and emotional factors are often the hidden catalysts (Moffitt, 2018).

Trauma and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

Studies from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2022) show that children exposed to violence, abuse, neglect, or parental substance misuse are significantly more likely to engage in crime later in life.

Trauma rewires the brain’s stress system, leading to impulsivity, hypervigilance, and aggression (Felitti et al., 1998). Without early support, these emotional wounds become behavioral patterns.

Emotional Dysregulation

Unaddressed anxiety, depression, or anger issues make young people vulnerable to antisocial behaviors. Many offenders are not “bad” but emotionally injured — reacting to pain with defiance or violence (Perry, 2006).

Identity and Belonging

Youth gangs often provide the sense of belonging missing from home or school. When society rejects them, criminal groups embrace them — offering identity, power, and community in exchange for loyalty (Decker & Pyrooz, 2011).

Mental Illness and Substance Abuse

Co-occurring mental illness and substance misuse (dual diagnosis) are prevalent among young offenders. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2022) notes that up to 70% of incarcerated youth meet diagnostic criteria for a mental health disorder.

Why Punishment Alone Doesn’t Work

Traditional punitive approaches — detention, incarceration, and criminal records — often exacerbate the very problems they aim to solve (Sherman & Strang, 2012).

The prison system, in many countries, has become a revolving door for traumatized youth who never received the care they needed.

Reinforcing Trauma

Detention often replicates early trauma: isolation, powerlessness, and humiliation. Instead of healing, young people internalize anger and mistrust toward authority (Bloom & Farragher, 2010).

Lack of Rehabilitation

Few correctional facilities offer structured mental health care, vocational training, or post-release support. Without therapy or reintegration programs, relapse into crime is almost inevitable (Lipsey & Cullen, 2007).

Economic Cost of Incarceration

The World Bank (2021) estimates that the annual cost of youth incarceration can exceed $30,000 per offender in some countries — far higher than investing in education or therapy-based prevention programs.

Moral and Social Costs

Punishment without healing fractures communities and perpetuates intergenerational trauma (Alexander, 2010). A society that punishes its youth instead of healing them mortgages its own future.

Therapeutic Interventions: Healing the Mind to Rebuild Society

Therapeutic intervention refers to structured mental health programs — counselling, psychotherapy, group therapy, and community healing initiatives — that address the psychological, emotional, and social drivers of youth crime.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) for Offender Rehabilitation

CBT-based programs help young offenders recognize negative thinking patterns and learn problem-solving, impulse control, and empathy.

Meta-analyses by the American Psychological Association (APA, 2020) show that CBT reduces reoffending by up to 30% when integrated into justice systems.

Trauma-Informed Care (TIC)

A trauma-informed approach begins by asking not “What’s wrong with you?” but “What happened to you?” (SAMHSA, 2014).

By acknowledging trauma’s role, professionals create safer spaces for healing. TIC programs in U.S. juvenile courts and African youth centers have demonstrated reductions in violent behavior and recidivism (Marrow et al., 2012).

Family Systems Therapy

Because youth behavior reflects family dynamics, interventions must involve parents and caregivers. Family therapy restores communication, resolves intergenerational conflict, and rebuilds trust — especially crucial in cultures where family honor and cohesion are central (Carr, 2019).

Community-Based Support Circles

Community peer mentorship and restorative justice circles are traditional African approaches gaining global recognition.

In Kenya and South Africa, youth are encouraged to make amends, participate in skill-building, and serve their communities as part of rehabilitation (Skelton & Batley, 2008).

School Mental Health Programs

Early school-based interventions that teach emotional regulation, empathy, and coping skills prevent at-risk students from escalating into delinquency (Durlak et al., 2011).

MindCarers’ proposed “Schools for Emotional Intelligence” initiative aims to equip teachers and counselors with skills to detect and respond to early signs of distress.

The Role of Corporate and CSR Stakeholders

Corporate organizations have both the moral duty and economic incentive to invest in youth mental health as part of their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) portfolios.

Youth Mental Health = Future Workforce

Today’s at-risk youth are tomorrow’s workforce. By supporting community mental health programs, companies secure a healthier, more employable generation (ILO, 2021).

CSR Programs with Measurable Impact

Businesses can fund mental health education in schools, sponsor therapy access for at-risk youth, or partner with NGOs for reintegration programs.

For example, a CSR-backed “MindCarers Community Healing Fund” could support local NGOs providing therapy and life-skills training to juvenile offenders.

Reducing Crime Improves Business Stability

Youth violence destabilizes communities, discourages investment, and erodes market trust (UNDP, 2020).

When businesses invest in crime prevention through mental health, they create safer environments for commerce and growth.

Building Brand Reputation

Consumers increasingly support socially responsible brands. CSR-driven mental health interventions enhance corporate image, stakeholder trust, and long-term profitability (Porter & Kramer, 2011).

The Policy Imperative: From Justice to Healing

Governments and policymakers must move from retributive to rehabilitative justice, embedding mental health within youth justice frameworks (UNCRC, 2021).

Mental Health Screening in Juvenile Systems

Every youth entering the justice system should receive a psychological evaluation and access to care, as recommended by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, 2021).

Integration into Education Policy

Mental health literacy and life-skills training should be embedded in national curricula.

Countries like New Zealand and Finland already treat mental well-being as part of civic education, reducing youth delinquency rates significantly (OECD, 2021).

Public-Private Partnerships

Collaboration between governments, corporations, NGOs, and digital platforms like MindCarers can amplify reach and sustainability.

Mobile therapy tools, helplines, and digital counseling hubs make scalable intervention possible even in resource-limited settings (ITU, 2022).

Restorative Justice Policies

Policies that promote mediation, restitution, and therapeutic rehabilitation — rather than incarceration — restore dignity and trust in both youth and community (Zehr, 2002).

The African and Global Opportunity

Africa, with its strong community values and youthful population, has a unique opportunity to lead the global transformation from punishment to healing.

Over 60% of Africa’s population is under 25, making youth mental health one of the most urgent development priorities (AfDB, 2022).

Platforms like MindCarers.com are pioneering culturally sensitive, tech-enabled, and community-integrated models of care that blend digital therapy, lay supporter training, and youth empowerment.

The Economic and Social ROI of Therapeutic Programs

Mental health interventions are not just socially effective — they are economically sound.

A World Health Organization (WHO, 2016) study found that every $1 invested in mental health prevention yields a $4 return in improved productivity, social stability, and reduced justice costs.

In Nigeria, the cost of juvenile incarceration per youth could fund a year of therapy and vocational training for ten others.

The ROI is not just financial; it’s generational — creating communities that heal instead of punish.

MindCarers’ Vision: Healing Minds, Restoring Futures

At MindCarers.com, we envision a world where no young person is defined by their worst decision.

Our programs integrate digital therapy access, corporate wellness, and community education to create holistic mental health ecosystems.

Through the upcoming MindCarers Youth Resilience Initiative, we aim to:

Provide digital counseling access to at-risk youth.

Train teachers, parents, and community leaders in trauma-informed care.

Partner with businesses and CSR leaders to fund reintegration programs.

Collaborate with governments for policy inclusion and advocacy.

By bridging mental health, education, and justice reform, MindCarers is redefining what it means to create safer, stronger, and more compassionate societies.

Conclusion: From Crime to Care — A New Paradigm for Humanity

Reducing youth crime is not only about law enforcement — it’s about healing the wounded hearts that laws alone cannot reach.

When society replaces judgment with understanding and punishment with therapy, it plants the seeds of transformation.

Therapeutic mental health programs can help young people rediscover identity, purpose, and hope — turning potential offenders into community leaders.

The future of youth justice must be built not on walls of fear, but on bridges of empathy.

In this new paradigm, healing becomes justice, and care becomes prevention.

And at the heart of this movement stands a question every nation must answer:

Do we want to punish our youth — or protect our future?

References (APA 7th Edition)

African Development Bank (AfDB). (2022). African Economic Outlook 2022: Supporting Climate Resilience and a Just Energy Transition in Africa. AfDB.

Alexander, M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. The New Press.

American Psychological Association (APA). (2020). Reducing recidivism through cognitive behavioral interventions. APA.

Bloom, S. L., & Farragher, B. (2010). Destroying sanctuary: The crisis in human service delivery systems. Oxford University Press.

Carr, A. (2019). Family therapy: Concepts, process and practice (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022). Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Leveraging the Best Available Evidence.

Decker, S., & Pyrooz, D. (2011). Gangs, terrorism, and radicalization. Journal of Strategic Security, 4(4), 151–166.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., et al. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., et al. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258.

International Labour Organization (ILO). (2021). Global Employment Trends for Youth 2021: Technology and the future of jobs.

International Telecommunication Union (ITU). (2022). Digital transformation for development in Africa.

Lipsey, M., & Cullen, F. (2007). The effectiveness of correctional rehabilitation: A review of systematic reviews. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 3, 297–320.

Marrow, M. T., Knudsen, K. J., Olafson, E., & Bucher, S. E. (2012). The value of implementing trauma-informed care in juvenile justice systems. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 5(3), 257–270.

Moffitt, T. E. (2018). Theories of delinquency and development. In Crime and Justice: A Review of Research, 46, 3–41.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2021). The well-being of students: Bridging school, home and community.

Perry, B. D. (2006). The neurosequential model of therapeutics. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 14(3), 38–43.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 89(1–2), 62–77.

Sherman, L. W., & Strang, H. (2012). Restorative justice: The evidence. The Smith Institute.

Skelton, A., & Batley, M. (2008). Charting progress, mapping the future: Restorative justice in South Africa. Institute for Security Studies.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884.

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). (2021). General Comment No. 25 on children’s rights in relation to the digital environment.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2020). Youth and sustainable development in Africa.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2023). Global Study on Homicide: Youth Violence Report.

World Bank. (2021). World Development Report 2021: Data for better lives.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2016). Investing in treatment for depression and anxiety leads to fourfold return. WHO Press.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2022). Youth violence: Key facts. WHO Fact Sheet.

Zehr, H. (2002). The little book of restorative justice. Good Books.

What's Your Reaction?